The Good, the Bad and the Ugly of Eliminating Third Party Data

Let’s Admit It: Third-Party Targeting Wasn’t All That Great

Before we bemoan the end of third-party targeting, let’s be honest about its usefulness. On the whole, it kind of sucked.

Ever notice how there were way more people that the data companies labeled as ‘auto-intenders’ than there were cars sold each year? It’s because behavioral data is inherently flawed. Lots of people, myself included, read about the BMW M5 or the Ferrari Portofino, but that doesn’t mean we’re ever going to buy one. Aspirational shopping isn’t intent, it’s a hobby.

Or consider people who are relatively new homebuyers. It’s human nature to visit a real estate site to see how other houses in your area are selling. This behavior doesn’t mean these consumers are about to buy another house, they’re simply seeking validation of the massive investment they just made.

Or consider people who are relatively new homebuyers. It’s human nature to visit a real estate site to see how other houses in your area are selling. This behavior doesn’t mean these consumers are about to buy another house, they’re simply seeking validation of the massive investment they just made.

And how is third-party data classified, anyway? Which criteria do data companies use to label someone a fashion enthusiast or a luxury mom?

How many behaviors are required in order to be so labeled? How often are those criteria refreshed? Marketers had absolutely no insight into this vital process, which means they were stuck paying high CPMs to target users who already converted.

Finally, behavioral and intent data is inherently low-funnel and that makes it highly problematic. To begin, every marketer often says, wireless services are competing for the same users, making it very difficult to break through the noise. And getting bombarded with the same types of ads is a pretty miserable experience for the consumer, especially if he or she has already converted. Worst of all, competing at that level forces the marketer to compete based on price, rather than the inherent value of the product itself. These are significant drawbacks, and advertisers shouldn’t mourn the loss of third-party cookie targeting.

Validating Needs

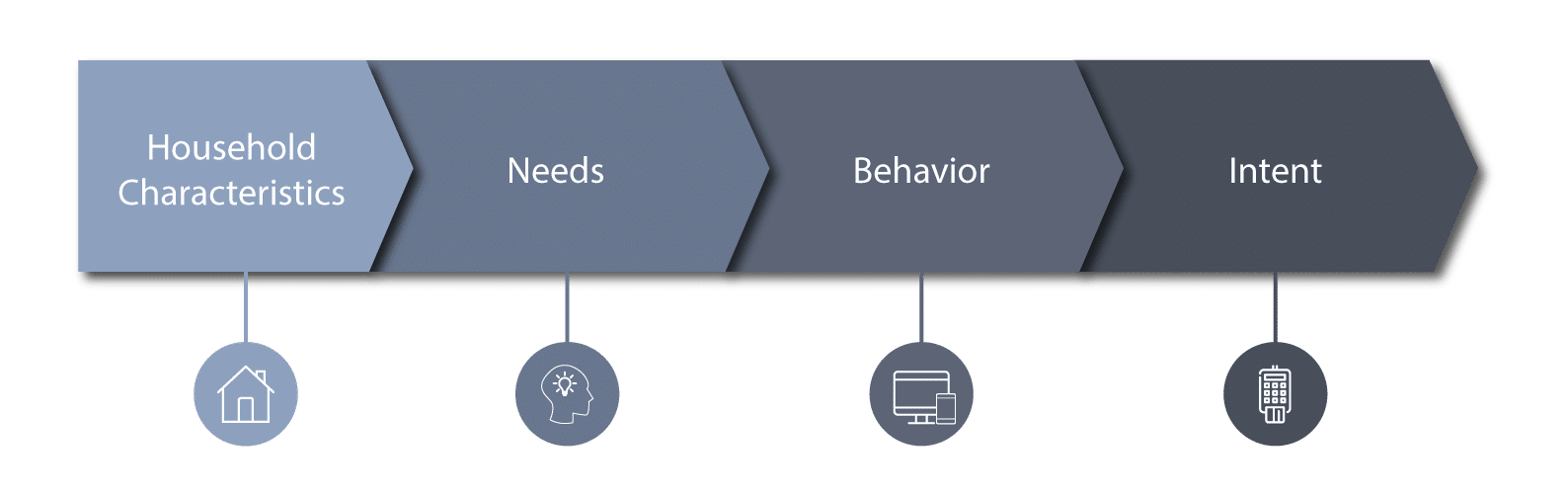

But there are other, super strategic benefits to household characteristics data that address the challenges that have long plagued marketers. First, household characteristics allows marketers to identify every household that can potentially buy a product you’re offering. There’s no purpose in offering back-to-school promos to people who don’t have children or new snow tires for consumers who don’t own cars.

In other words, household characteristics validate whether a need exists before adding a particular audience member to the targeting pool. For marketers, it means the end of spending money to target aspirational shoppers (who are likely to navigate directly the BMW or Ferrari website anyway).

Second, household characteristic data allows marketers to target at the upper funnel, rather than at the bottom, where the competition is fierce. Focusing on the upper funnel also means you’re the first to present a product or service to a consumer and become the benchmark for comparisons to other brands. Wouldn’t you rather focus the conversation around features and benefits rather than cost?

Characteristic-Driven Behaviors

If a need exists — if a household has children present — behaviors are far more predictable. For instance, households with kids will purchase school supplies, children’s books, children’s clothes, toys, college savings plans, life insurance, and so on. Households with cars will purchase fuel, accessories, auto insurance, and other auto-related items. They will make predictable purchases because the need for such items stems from stable household characteristics.

Need-Driven Intent

In traditional cookie-based targeting behavior is used as a proxy for intent. If a consumer visits a site for children’s clothes, she must be in-market for children’s clothes now. This assumption is profoundly flawed, in part because it can’t distinguish aspirational shoppers from those who will actually make a purchase, and in part, because it focuses solely on the lower funnel.

By its nature, household characteristic data focuses on the upper funnel: this is a household with children, eventually, they will buy clothes for those kids. The intent is absolutely assured, the timing of the purchase is not.

Targeting by household characteristics requires marketers to focus their efforts on building a relationship with customers over time and telling their brand stories (e.g. “We founded our company because we wanted our own kids to have clothes that are classic, but durable and easy to wash, when we couldn’t find any we decided to make them ourselves”). If you can tell a good brand story and it resonates with consumers, they’ll seek out your brand when it comes time to purchase.

And this is precisely the reason why marketers should focus on their upper funnels. It allows you to position your products based on quality, and speak directly to consumers who have a validated need for what you sell.

Frankly, I’ve never been a fan of the kinds of marketing tactics third-party targeting requires. Competing on price devalues a brand. And it relies on tricks and ploys to create a sense of urgency — “buy now and get an additional 7% off,” or “better hurry, only 5 left in stock.” This is no way to build a sustainable brand.

/ Søren H. Dinesen, CEO Digiseg – Shd@digiseg.io